My friend Maria Rickert Hong and I just discovered something interesting about the CDC’s data on autism rates and prevalence.

You may have seen the email we sent out recently about the new autism rates reported by the CDC . . . The new numbers are alarming.

1 in 36 children has an autism spectrum disorder.

On their website, the CDC tells us that this is up from 1 in 88 in 2009.

Maria and I were chatting and both of us could have sworn that the autism rate reported by the CDC in 2009 was 1 in 150.

So, we checked it out. And we were right. In 2009, the CDC did report the rate as 1 in 150 (see internet archives below).

And this is where we found a really interesting phenomenon with the CDC data on autism prevalence.

We both jumped to the conclusion that the CDC went back, cherry picked data and adjusted the rate to make the growth of autism look higher in the past, to perhaps blunt the effect of the jaw-dropping new rates they just released. (Sadly, neither Maria nor I have a whole lot of trust in the CDC in this post-COVID world, so, we assumed the worst. I think we’re not alone.)

But, being the diligent librarian researcher types that we are, we took the time to look into why the CDC’s data for 2009 changed. Here’s what we found:

Down the Memory Hole

I remember the 2009 CDC autism statistic “1 in 150” so clearly because I cited it in my book, A Compromised Generation (published in 2010). I was very meticulous with my citations when I wrote that book, and I verified that it was indeed reported to be 1 in 150 in 2009 and that this CDC statistic was backed by solid medical literature.

I went back to find the webpage citation I referenced on the CDC website in 2009. It was gone. No big deal. People change URLs all the time.

So, what do you do when a webpage is no longer up? You use the Wayback Machine, also known as the Internet Archive, or the place where webpages are archived so that their history and existence in time is documented and searchable. You can find EVERYTHING on the Wayback Machine. I did not find this page, but I did find archived CDC autism prevalence pages going back to 2004.

Here is the autism prevalence page that can be searched in the internet archives: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism

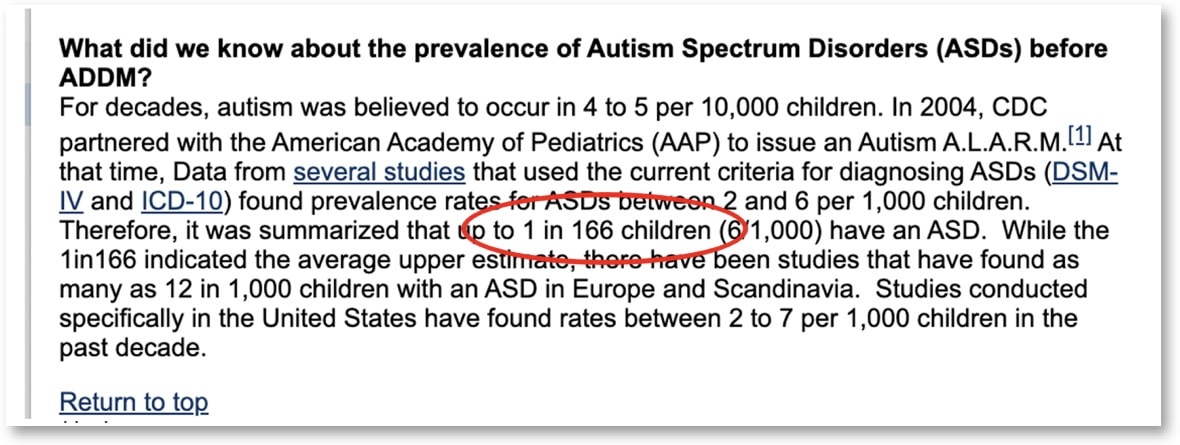

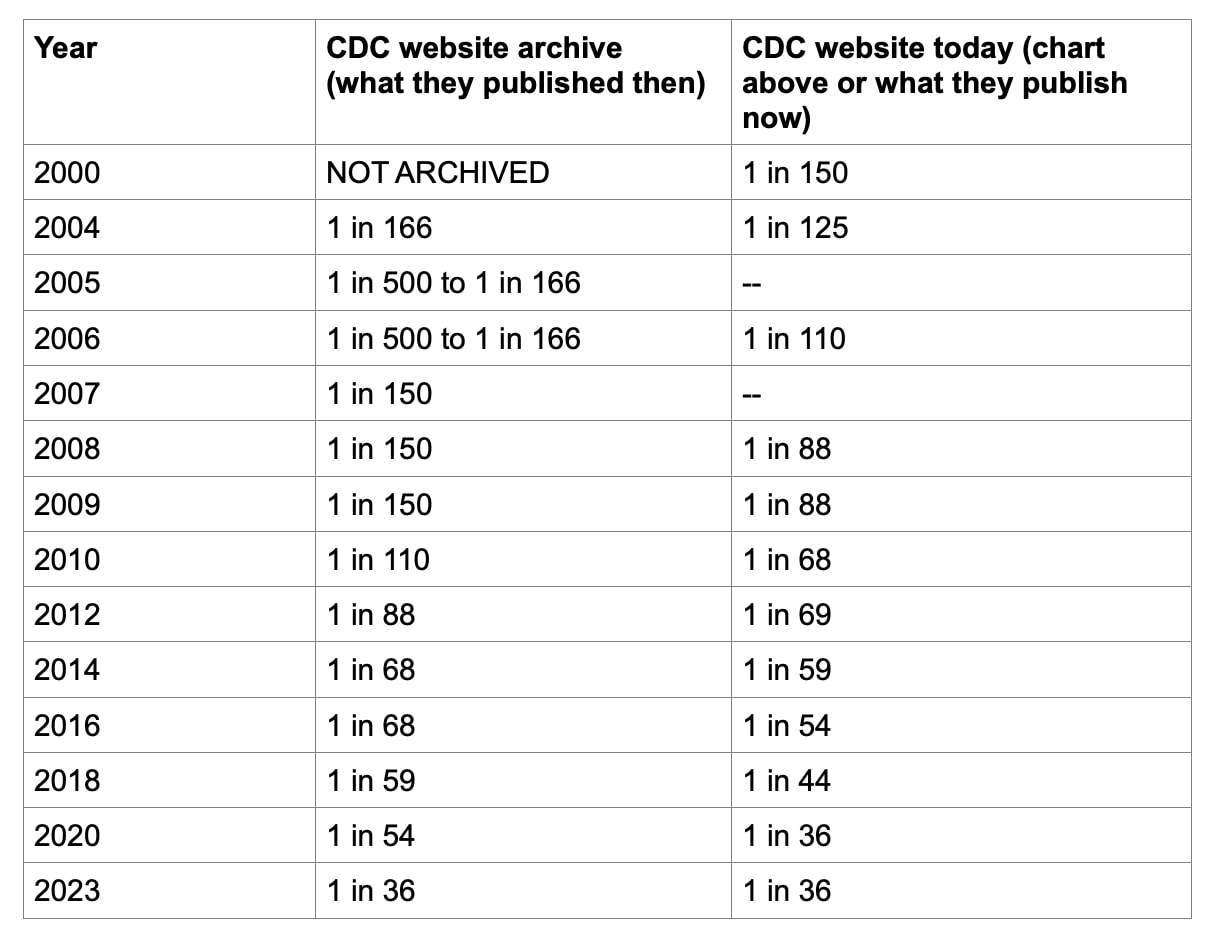

If you go back and look at the archived CDC pages, the numbers in their archives are different from what they list now. For example:

In the archives, the 2004 prevalence number is listed as 1 in 166. Today they list the 2004 number as 1 in 125.

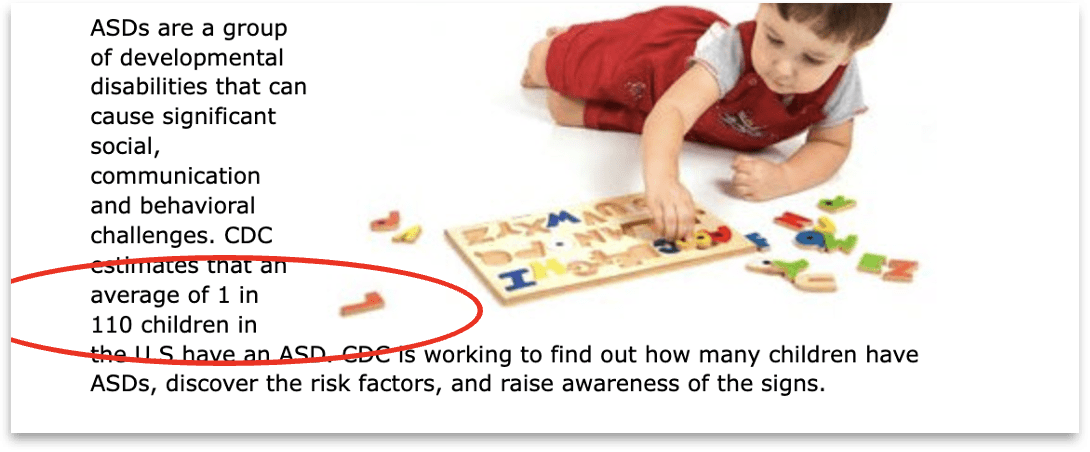

In the archives, the 2010 prevalence number is listed as 1 in 110. Today, the 2010 prevalence number is 1 in 68.

See screen shots below.

2004 Archived CDC Webpage

2010 Archived CDC Webpage

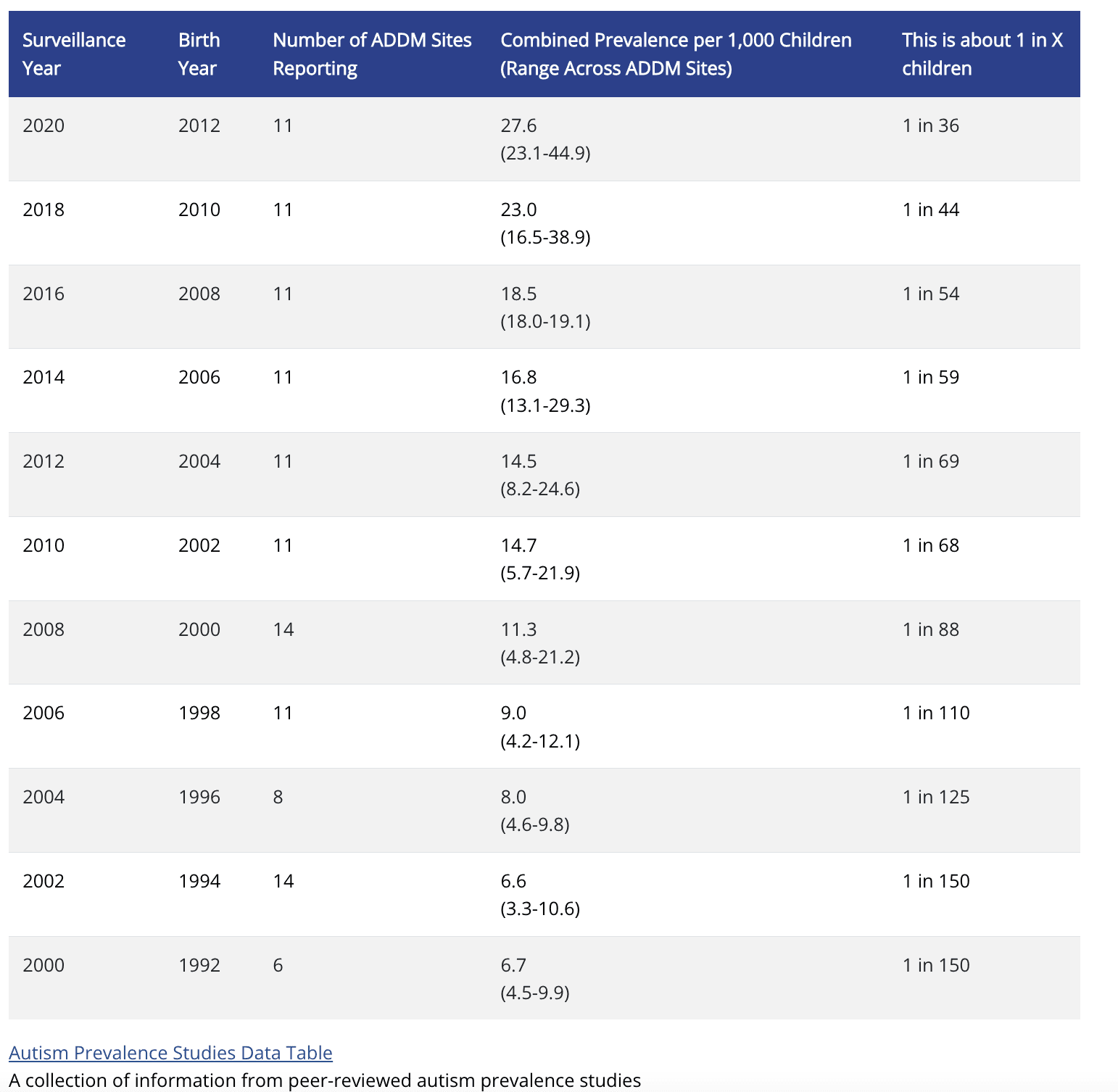

Here is what the CDC offers today in terms of autism rates from 2000 to 2020. Note, they only provide data going back to 2000.

We searched the internet archives for records of what the CDC *actually* reported at the end of each year. I’ve listed most of the years below. You’ll note the discrepancy between the archived CDC prevalence webpages and the reported prevalence today.

Do you see the discrepancy between the reported prevalence on the archived pages and the updated data?

The overall impact of the discrepancy (the CDCs characterization of the data) is that it kinda makes it look like autism was more common in prior years. That felt a little suspicious.

We immediately wondered . . . Did the CDC memory-hole the official autism rates for 2009?

The conspiracy theorists in us wondered if the CDC was trying to “slow-down” the obvious and concerning growth rate of autism (flatten the curve) by memory-holing the original data they reported and cherry-picking data that flattened the curve. So, we dug deeper.

It turns out that much of that discrepancy is due to the fact that they updated the historical prevalence data as new epidemiological research came out.

So, no memory-hole conspiracy here, folks.

But still . . . something wasn’t sitting right with me about the historical autism data and how the CDC presents it on the website.

And then it hit me.

While the CDC did not “memory-hole” the official CDC data on children with autism, they do routinely update the prevalence numbers within a few years after reporting. And in almost every single update, the “new numbers” were actually substantially HIGHER than the original number.

This means that we can reasonably expect the official 2023 CDC number of 1 in 36 children diagnosed with autism to be more accurately updated in a year or two with a much higher number.

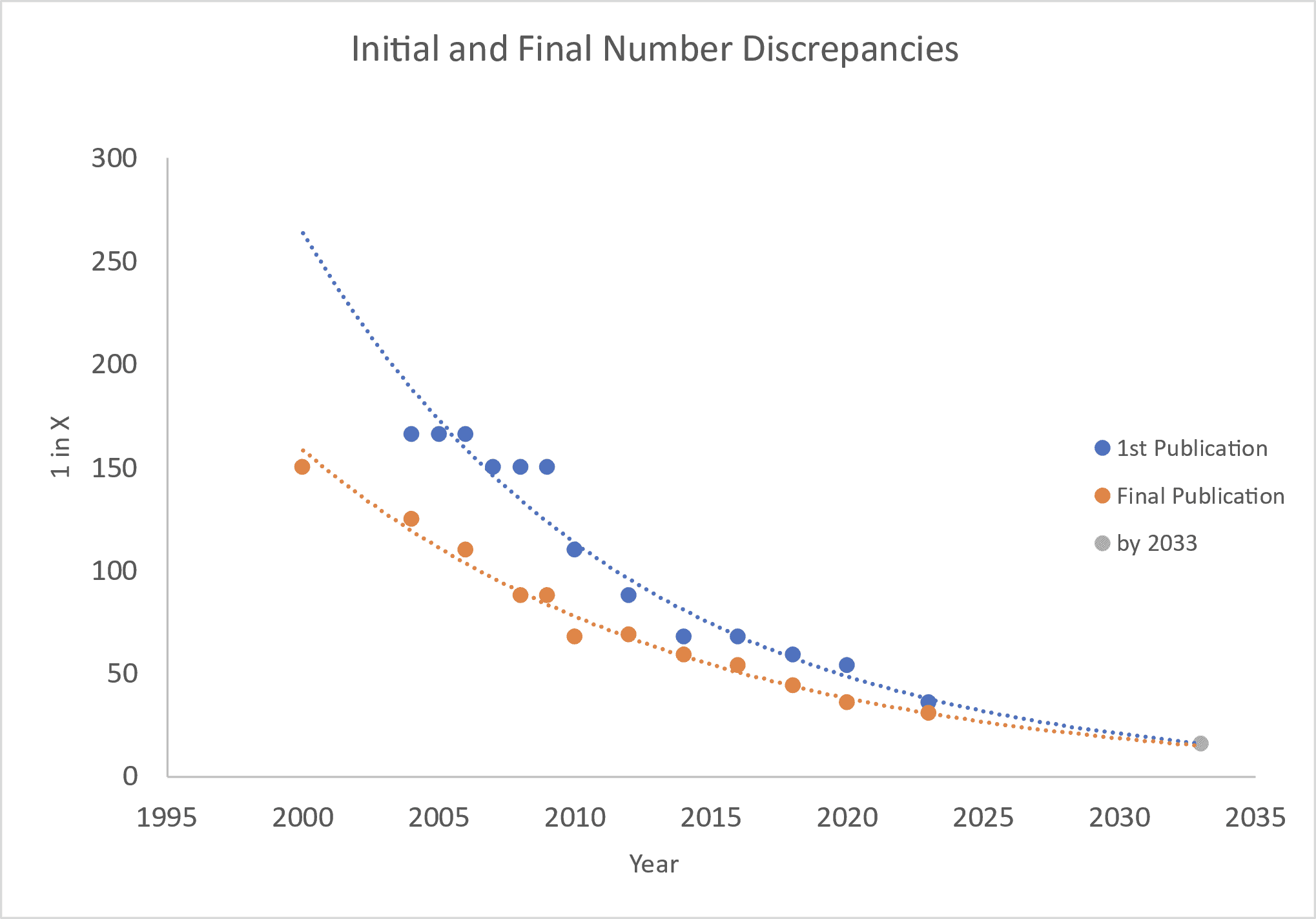

I asked our senior scientist, Dr. Randy Reiserer, to help me estimate what the expected “new numbers” (or update to 2023’s numbers) might look like in a couple of years. I also asked him to project the trends forward (based on past data and trends).

Using statistical methods, this is what the trend shows:

Based on the CDC’s past pattern of updating prevalence numbers with more accurate data, the 2023 autism prevalence number may soon be updated to be 1 in 31.

And continuing this trend on (as the chart above shows), when we get to 2033, it will be 1 in 16 children with an autism spectrum diagnosis (an estimated 6.25% of children and 9% of boys!)

Nearly 1 in 10 boys will have autism in 2033.

Let me say that again.

Nearly 1 in 10 boys will have autism in 2033.

Let.

That.

Sink.

In.

Let’s go deeper down the memory hole.

All of this data I’ve been throwing at you is only addressing autism prevalence since 2020.

If you go back just a few decades earlier, the meteoric growth of this diagnosis in the American pediatric population is breathtaking.

We are talking about a change from 2 or 3 cases in 10,000 to 1 case in every 36 kids in just a few decades.

And now we’re looking at 1 in 16 kids by 2033?!

Sadly, historical data (before 2000) is not represented on the CDC website. What if the CDC seriously represented the data change from the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s to now?

Here are a few examples of the studies that the CDC does not include on their website:

- The first robust studies of autism prevalence reported a rate of about 2 to 4 cases per 10,000 children (1 in 5,000 to 1 in 2,500) See: Lotter, 1966; Rutter, 2005; Treffert, 1970.

- The Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry published a study in September 2000 that put the prevalence of autism between 1989 and 1999 at 1 in 2,000, and 1 in 1,000 if you include Aspergers and autism together.

- Another study published in the Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, in July 2003, cites that the autism prevalence grew from 3 per 10,000 (~1 in 3,300) in 1991-1992 to 52 per 10,000 (1 in 200) in 2001-2002.

And there are more studies published pre-2000 showing that autism was indeed rare.

A lot of this increase is “explained away” by the experts as expanding diagnostic criteria, better outreach and better diagnosis. And those things have, indeed, resulted in “capturing” more cases of autism. But not enough cases to take us from 2 or 3 cases in 10,000 to 1 in 150 and certainly not to 1 in 36 (or, gasp, 1 in 31!).

I know people in 1970 had bad taste in clothes and hairdos but they weren’t totally out to lunch, and they didn’t “miss” 138 kids with autism for every 3 children they diagnosed. Especially kids who were severe or moderate (40% of cases). I’ll grant you, we definitely missed some milder cases, but we didn’t miss 55 severe to moderate kids (40% of the kids we apparently missed) for every 3 diagnosed children.

Those kids weren’t “overlooked” because we didn’t have proper diagnostic categories or because we were calling it something other than autism. That just doesn’t make sense.

The “better/expanded diagnosis” theory has been challenged by many. JB Handley, in his book How to End the Autism Epidemic, provides a really logical and cogent illustration of how the “missed diagnosis” hypothesis just doesn’t hold water.

Handley says:

“I’m approaching fifty years old, and as a child, I’d never seen or heard of even one peer with autism. Ask any teacher, doctor, nurse, or coach who has been working for three decades or more and you’ll always hear the same thing: something new and very different is happening with children today. My teenage children know of dozens of kids with autism, and schools are bursting at the seams with special education classes. . . A simple question refutes that narrative [that these children with autism have always been there]:

“Where are all the adults with autism? . . . Let’s do the quick math: Fifty-four percent of the US population is over the age of thirty-five. That’s roughly 174 million people. If one in thirty-six of those adults had autism, that’s 4.8 million American adults with autism—4.8 million adults over the age of thirty-five who have a disabling condition that makes independent living a challenge for all but the mildest of cases.”

Handley goes on, “There is no data anywhere that supports an adult autism number anywhere close to 4.8 million.” (Handley, How to End the Autism Epidemic, 17).

Still don’t believe me that the autism rate is *actually* spiraling out of control?

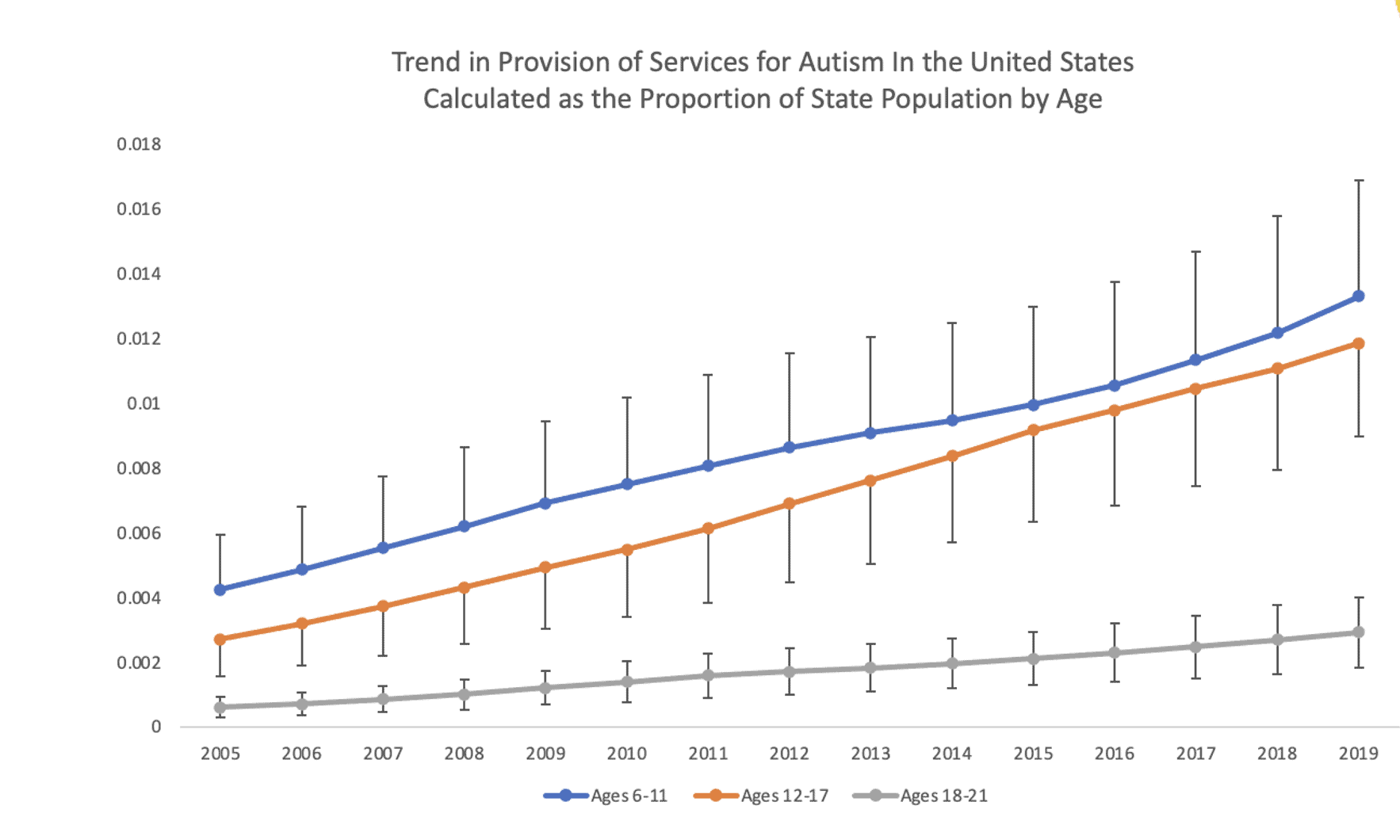

Take a look at the U.S. Department of Education IDEA data analysis that our Senior Scientist, Dr. Randy Reiserer, performed last year.

U.S. Department of Education IDEA data, compiled by Randall Reiserer, PhD, 2022.

What is this chart I’m looking at? This is the U.S. Department of Education IDEA data which documents increases in the services in school provided to autistic children over time and state-by-state across the U.S.

When you plot this data over time, you see an almost straight line that steadily rises year after year. To get such a result, one would have to hypothesize small, incremental and uniform improvements in diagnostic capabilities accrued each year between 2005 and 2019. For the line to look like this, the “diagnostic improvements” would have to be relatively uniform across states.

In other words, when a diagnostic innovation was made in one state, it would have had to spread to all 50 states fast enough to influence the statistics of all states in each successive year. Such a thing is clearly impossible (and the incremental changes/shifting categories between DSM-IV and DSM-V doesn’t explain it either). We have a well-established 17-year lag in health innovation from benchtop to clinic, but autism diagnostics tools and methods spread instantly?

Why am I telling you all this?

Because we must be vigilant and aware of any intentional efforts to normalize the very high prevalence and growth rate of autism and developmental delays.

Impacted families (increasing by the second in this country!) need our help now. And dismissively patting them on the head and telling them that “autism has always been here” doesn’t do anyone any good.

We must stay alert to any attempts to memory-hole, cherry-pick or otherwise distort the numbers (say, for example, not dealing with data before 2000).

We must not allow ourselves to think that “autism has always been here.” As if it’s just a naturalistic thing that has always affected 3-4% or more of the pediatric population. Otherwise, when the CDC “updates” their numbers in 2033 with the rate of 1 in 10 boys, we might not notice the difference between 4% and 10%. We might lose our sense of alarm. Of urgency. Of the need for action.

My last thoughts

Did we “miss” or not diagnose some of the kids with autism in the past? Definitely.

Did we “miss” all these kids before?

That’s not possible. Don’t let them tell you that. That’s a lie.

Maybe instead of shrugging our shoulders and saying autism rates have always been here, we should start asking why autism, a condition we are told is largely “genetic” in origin, is even increasing at all?

Genetic conditions don’t explode exponentially.

Don’t let them normalize this.

Demand Answers.

Demand Answers for this Epidemic.

Sincerely,

Beth Lambert

Founder and Executive Director, Epidemic Answers

P.S. We’re hot on the trail of some really powerful answers from our CHIRP™ Study. Have you participated yet?

If the CHIRP™ Study is not for you (you need to be a parent of a child between the ages of 1 and 15) we sure could use your help supporting the study with a donation (thank you!).

About Beth Lambert

Beth Lambert is a former healthcare consultant and teacher. As a consultant, she worked with pharmaceutical, medical device, diagnostic and other health care companies to evaluate industry trends.

She is the author of A Compromised Generation: The Epidemic of Chronic Illness in America’s Children (Sentient Publications, 2010). She is also a co-author of Epidemic Answers’ Brain Under Attack: A Resource for Parents and Caregivers of Children with PANS, PANDAS, and Autoimmune Encephalitis.

In 2009, Beth founded Epidemic Answers and currently serves as Executive Director. Beth attended Oxford University and graduated from Williams College and holds a Masters Degree in American Studies from Fairfield University.

Still Looking for Answers?

Visit the Epidemic Answers Practitioner Directory to find a practitioner near you.

Join us inside our online membership community for parents, Healing Together, where you’ll find even more healing resources, expert guidance, and a community to support you every step of your child’s healing journey.

Sources & References

Blaxill, Mark, et al. Autism Tsunami: the Impact of Rising Prevalence on the Societal Cost of Autism in the United States. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022 Jun;52(6):2627-2643.

Carey, Benedict. Study Puts Rate of Autism at 1 in 150 U.S. Children. The New York Times, 9 Feb 2007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Accessed 4 Apr 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. Accessed 24 Mar 2023.

Gurney, J.G., et al. Analysis of prevalence trends of autism spectrum disorder in Minnesota. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003 Jul;157(7):622-7.

Li, Q., et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children and Adolescents in the United States From 2019 to 2020. JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Sep 1;176(9):943-945.

Lotter V. Epidemiology of autistic conditions in young children. Social Psychiatry. 1966;1(3):124–135.

Maenner, M.J., et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years – Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021 Dec 3;70(11):1-16.

Rosen, N.E., et al. The Diagnosis of Autism: From Kanner to DSM-III to DSM-5 and Beyond. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021; 51(12): 4253–4270.

Rutter M. Aetiology of autism: Findings and questions. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49(4):231–238.

Tanguay, P.E. Pervasive developmental disorders: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 Sep;39(9):1079-95.

Treffert, D.A. Epidemiology of Infantile Autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1970;22(5):431-438.

Waterhouse, L. Autism overflows: increasing prevalence and proliferating theories. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008 Dec;18(4):273-86.

Resources

Handley, J.B. How to End the Autism Epidemic. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018.

Lambert, Beth. A Compromised Generation: The Epidemic of Chronic Illness in America’s Children. Sentient Publications, 2010.