Autism is a term that is reasonably new in the modern lexicon. While the term autism was first coined in 1912, a neurological presentation that has similar characteristics to what we call autism has likely been around for a very long time in human history. However, this type of neurological presentation (and associated behaviors) was exceedingly rare in the past. I mean, the 2-in-10,000 kind of rare.

Has Autism Increased Just Due to Better Diagnosis?

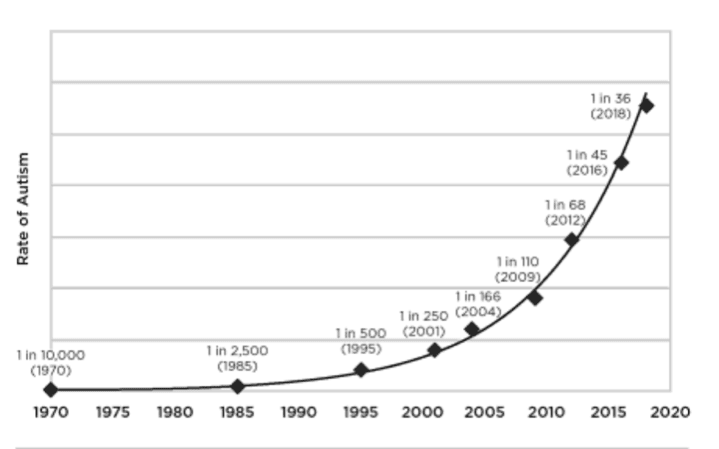

Yes, we are better at diagnosing, but this does not explain the jump from 2 in 10,000 to 1 in 31 in just 50 years. There are people that will tell you that we have always had 1 in 31 children with autism in the human population . . . that 3% of people have always been autistic, despite the fact that there is no epidemiological evidence to support this statement.

No one challenges the real rise in life-threatening food allergies in children over the last 50 years. We can track hospital and ER admissions, the results of validated laboratory tests, and deaths from anaphylaxis to objectively conclude that the rate of life-threatening food allergies has grown exponentially in recent decades.

With autism, the diagnosis is subjective and based on a set of criteria used by a diagnostician who employs personal judgement to determine a positive/negative diagnosis. What’s more, the diagnostic criteria have changed over time, making the waters muddier. There has never been an objective diagnostic test like a blood test that would help make the diagnosis indisputable and thus easier to track prevalence over time. As a result, the conventional narrative is that we’ve always had this much autism, it’s just that we “missed” them. We didn’t diagnose them.

[As an aside, there is now a blood test that has been developed to help identify children with autism more objectively. This should help.]

If You’re Over 40, How Many Kids with Autism Did You Know When You Were a Kid?

Autism–the word, the experience, the diagnosis, the awareness–burst onto the scene in the 1980s and became more generally known thanks to the film Rain Man in 1988. Before that, most people had never heard of it. Ask anyone over 40-years-old if they remember children with autism in their elementary, middle or high schools.

Most people will tell you that they don’t remember knowing anyone with autism or even anyone with a set of symptoms that looked like autism but was called something else. And if they did, it was one person that they knew of . . . in their whole life. But ask that 40-year-old how many children they know with autism today, and they can probably count several . . . maybe more than a dozen that they know of personally.

When I was in middle school, I volunteered at a special-education program that would run fun events for elementary-aged children with special needs. This was in the late 1980s. That organization served dozens of children with special needs in my area. There was not one child with autism served by that organization. Not one. Nor were there any children who had behaviors or patterns like looked like autism and were just called something else. There were children with Down Syndrome, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, brain injuries. But no autism. No children with features of autism—no stimming, no echolalia or scripting, no sensory defensiveness, no elopement. It wasn’t present in my community.

Remember, about 40% of children with autism are severe enough that you would not miss the outward, objectively observable signs mentioned above. I’m not saying autism didn’t used to exist before the 1980s. It did. It’s just that it wasn’t present in most communities, and it certainly wasn’t present in every classroom the way it is today.

Ask someone over 40:

- When you were growing up, did you know any children in your community that were nonspeakers?

- When you were growing up, did you know any children in your community that stimmed, flapped their hands or banged their head (commonly recognizable behavioral characteristics of moderate to severe autism)?

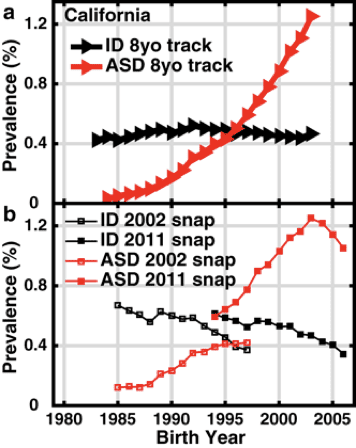

Figure 1. Nevison, C.D., Blaxill, M. Diagnostic Substitution for Intellectual Disability: A Flawed Explanation for the Rise in Autism. J Autism Dev Disord 47, 2733–2742 (2017).

Most people today know someone with autism, and usually several people. It is so common now that it has become completely normalized, and people act as if it has always been like this. And you will find article after article in the legacy media (New York Times, Washington Post, NBC, ABC, CBS, NPR) that will tell you that “There’s no true increase in autism, we’re just better at diagnosing.”

While it is true that we are definitely better at diagnosing autism today then in 1980 or 1990, it still does not account for the total increase. Every time someone brings up the idea of “diagnostic substitution”—the idea that autism has always been here, but that we just called it something else (like “intellectual disability”), I share this publication (see chart at left) based on IDEA data to illustrate how diagnostic substitution accounts for *some* but not all new cases. And certainly not the skyrocketing growth rate of ASD since 1990. The rates of autism are rising dramatically, no matter how much you try to explain it away.

It’s an epidemic. We must acknowledge this.

What Are the Statistics?

The statistic for autism in the 1970s was 2 in 10,000. That sounds about right. That fits my experience. I didn’t have 5,000 people in my sphere of influence, but I would have needed to have approximately 5,000 people in my world in order to know one person with autism. I did know several people with Down syndrome, which is found in about 1 in 1,000 children (much less common than the 1 in 31 children diagnosed with autism today). This is the experience of pretty much anyone I talk to who is over 40 years old.

Figure 2. Handley, J.B. How to End the Autism Epidemic.

Today, the CDC puts the prevalence of autism at 1 in 36 children. Our research puts the number closer to 1 in 31, and in some geographies, such as California, the rates can be as high as 1 in 22.

Even if “autism” with a different name has been around for a very long time, we are seeing an absolute explosion in the number of children receiving this diagnosis every year.

If we widen the aperture beyond autism and include diagnoses like ADHD and learning disabilities, the number of children in the United States today who are “neurodivergent” (more on this term below) is estimated at 20%.

The Cost of Autism

Something is creating an increase in this neurological presentation in humans.

We did not have 20% of humans in any society at any time in recorded human history with this distinct cluster of neurological and neurobehavioral symptoms. It just wasn’t there. I don’t care what Stephen Silberman’s book Neurotribes says. Let the epidemiologists be the experts on this. They will tell you that autism was not always 1 in 31 children, or 1 in 22 children in California, no matter how loose the diagnostic criteria.

In no history in any universe ever would this be true, especially when you consider that at least 40% of people diagnosed with autism are considered moderate/severe and at least 27% are considered “profoundly” autistic (ranging by geography with 38% of children with autism in South Carolina being labeled “profoundly autistic”). Profoundly autistic is described as children who were “more likely to have self-injurious behavior or epilepsy and require around-the-clock supervision.” They didn’t “miss” all these kids with moderate/severe autism when they did their research in 1970 and found 2 in 10,000. Taking the growth rates from the last few decades and projecting forward, we will be at 1 in 16 children (and 1 in 10 boys) diagnosed with autism by 2033.

By 2033, our society will be asked to provide round-the-clock care and support for about 1 in 48 children (those who are severe/profoundly autistic, about 1/3 of those diagnosed with autism) and the rest of the children with autism will still need substantial care and support beyond what a typical child needs. How will parents work? Who will pay for that care? What will happen to these children when they become adults and there are no parents to care for them? This isn’t some far off scenario. This is less than 10 years away.

It is estimated that upwards of 85% of adults with ASD are unemployed. At present, our society is not equipped to support this population of impacted children, and even more so as they age and no longer have family to support them and care for them. Further, when a parent must stay home to care for a child with autism, that parent is unable to earn income they would otherwise be able to earn and needs to be supported by a spouse or family members.

A paper published in Science, Public Health Policy, and the Law in December 2023 estimated that the total population-wide ASD cost in the U.S. would reach $5.54 trillion/year by 2060. Yes, that is a T. It says TRILLION. For perspective, the GDP of the United Kingdom in 2023 was about £2.27 trillion (or $2.8 trillion U.S. Dollars). Read this next sentence slowly and let it sink in: In 2060, the cost of autism in the U.S. will be double the current GDP of the United Kingdom.

Why Is This Happening?

Maybe it’s time to take a moment and stop dismissing people who are raising the alarm bells about the escalating rates of autism. Maybe it’s time to take a moment to try and understand *why* this might be happening.

Before we can understand why autism is increasing, we must first understand what autism is.

What is autism, really?

Because our society at large doesn’t really understand what autism is, we are unwittingly perpetuating the autism epidemic and ignoring the true and urgent needs of people with autism.

Some people call the neurological presentation or cluster of symptoms that we call autism “neurodivergence” or they might identify with the term “neurodivergent”. Neurodivergent is a new term (that was coined in the oughts, building on the concept of neurodiversity) that includes people with autism, ADHD, some learning disabilities, and other neurodevelopmental or chromosomal conditions that impact the way a person’s brain works.

Most scientists agree that what we call “neurodivergence” is developmental (something that develops in utero or in the early years of life), although there is much debate about whether this “something that develops”, is due to genes (believed to be static, intractable) or environment (often actionable) or both. Depending on the specific condition, genes or environment may be more or less at play.

I would contend that the neurological presentation that we call autism, in most (but not all) cases, develops over time from myriad contributing environmental factors from pre-conception onwards. Usually, it is multi-generational and specifically involves influences pre-conception through the first few years of life and is due to a combination of genetics and a cumulative and synergistic load of environmental stressors. For some children (like those with Rett syndrome, fragile X or Down syndrome), a genetic or chromosomal component may feature prominently. For others, environmental factors play a larger role.

For example, there are certain genetics that might make an individual more vulnerable to developing autism, but interestingly, these may also be the same genetics that make one more vulnerable to developing Parkinson’s, depression, cancer, anxiety, or other conditions. This may have more to do with a person’s ability to methylate, detoxify, and process the environmental stressors that are a part of living in the modern world (but were not present in the pre-industrial age). Here and here are some good papers on that subject.

How Does Autism (or Most Cases of Neurodivergence) Develop?

When a fetus or child is developing and confronted with toxic or stressful assaults (heavy metals, psychological and physiological stress, petrochemicals, artificial light, endocrine disruptors, fungal, bacterial or viral infections, trauma and more), the child will always prioritize survival over development.

If a child has a finite amount of energy that their body has to work with on a daily basis, that energy will be shunted to survival needs (removing toxins, repairing damaged DNA, managing inflammation, mounting an immune response to combat chronic infections) over developmental needs (speech, vision, sensory processing, motor development). Read chapter 10 of Offspring: Human Fertility Behavior in Biodemographic Perspective for a solid explanation of this concept. It also explains why so many couples in the modern industrial world have trouble conceiving children.

So What Is Autism?

If we are going to use the term neurodivergence, I think it is extremely important that we understand what autism is and how it develops before we allow the term neurodivergent to be swept up into the boiling cauldron of American identity politics that is so divisive and charged in this socio-political climate.

The use of the term “neurodivergence” is well intentioned and extremely helpful for people who identify with this term. I also think the efforts made in recent years to understand the wide-ranging perspectives of people with autism is absolutely critical, especially those who are nonspeakers/not reliable speakers that have learned to communicate through spelling/letterboards.

While Autism Speaks, the largest and most well-funded autism NGO, hasn’t done a darn thing to help us understand why we are witnessing an autism epidemic, I will say that it has done a good job teaching people to be aware, sensitive and respectful of the needs of people who have autism. We still have a lot of work to do in this category, but awareness and educational campaigns have done a good job of explaining things like how:

- Some people with autism can have extreme sensitivities to light, sound, touch (and please do what you can to mitigate the sensory overload!)

- Some people with autism may not have the capacity to look you in the eye – many have ocular motor inflexibility and literally can’t look you in the eye, no matter how uncomfortable that may make you.

- The hand-flapping, spinning, or rocking that you see in some people with autism is a way for these individuals to calm and regulate themselves. They need to do that. Let them be.

- Some children with autism elope (run away) due to nervous-system dysregulation or sensory overload. This means, if unattended, they may run away and unknowingly put themselves in danger. Please look out for these children.

Notice that I said some people with autism. . . this is in reference to the fact that autism is a heterogenous diagnostic category and includes a wide range of symptom presentation and behaviors. Just because you have autism, doesn’t mean you stim; it doesn’t mean you can’t make eye contact; it doesn’t mean you can’t tolerate loud noises. As they say, if you know one person with autism, you know one person with autism.

The terms neurodivergent/neurodiversity/neurodivergence are helpful and supportive of neurodivergent people who need neurotypical people to understand that behind the behaviors and underneath the diagnosis, there is just a regular person who is like everyone else. That person has feelings, thoughts, dreams, aspirations, crushes, brilliant ideas, frustrations, talents, pain, sorrow, happiness, hilarity, a great sense of humor, and all the other wonderful things that make us the unique and beautiful humans that we are.

But let’s also remember that when you use the terms neurodivergent or autism or autism spectrum disorders you are talking about a group of people (children and adults) with wildly different sets of symptoms and presentations, capabilities, functionality and uniqueness. And it really serves no one to lump them all together.

Examples of People with Autism

Let me give you some examples, just using the label autism.

The diagnostic label of “autism” is applied to all of the following people:

- A 45-year-old woman who is married, with three children, gainfully employed with a 40-hour-a-week corporate job who experiences sensory sensitivity, mild social anxiety, and prefers hanging out with animals over people, but she just got her diagnosis at age 44, and suddenly these tolerable, but troubling, challenges in her life “make sense.”

- An 11-year-old boy who is a nonspeaker, is not toilet trained, experiences profound frustration and rages and injures himself to bleeding and bruising daily. His rages often result in injuries to his parents and younger sister.

- A 9-year-old girl who is highly verbal, extremely intelligent, academically successful, but experiences severe emotional dysregulation and is unable to safely and calmly express emotions like frustration, anger, and fear. Because of her emotional dysregulation and frequent behavioral outbursts, she struggles making friends and has developed depression because of her inability to connect to others.

- A 27-year-old woman who is a nonspeaker, unable to feed or clothe herself because her fine and gross motor capabilities are so severely impaired that she needs round-the-clock care. She lives in a group home and the cost of care has left her family deeply in debt.

- A 5-year-old boy who is highly verbal, but has such social anxiety, rigidity of behavior and visual fixations that he cannot be taken outside of his home without extreme and severe tantrums.

- A 33-year-old beloved entomologist, who works as a research scientist at a university. He is considered by his friends and family to be “quirky,” and peculiar in his interests, struggles with obsessive-compulsive disorder and is a compulsive handwasher, sometimes washing his hands 20 or more times a day.

All of these people –every single one—carry the diagnosis of “autism.” But what do they really have in common? We are giving people who are able to live full, independent lives, support themselves and their families and engage in civic life the same label as individuals who cannot use the toilet on their own, need round-the-clock care, and cannot communicate on their own due to severe motor impairments.

How is this diagnostic label truly serving these people?

So, what is autism, really?

Biomedical Root Causes of Autism

What if instead of giving people a label, telling them their experience is due to “genes” that they don’t have any control over, and sending them off with cookie-cutter therapies that aren’t that helpful, we spent time with them–as unique individuals–to find out about their health and medical history to look for ways to help them overcome their biggest challenges, as well as identify ways to support their greatest strengths?

What if instead of forcing nonspeaking children to participate in 40 hours a week of ABA therapy to teach them to use a fork and spoon and follow directions, we did some clinical and laboratory testing to find out why their motor cortex is “offline” making them not able to produce speech or grasp a fork or spoon. Or why their auditory processing speed makes it difficult for them to follow directions.

Maybe we could look a little deeper and figure out why their sensory system is flooded with noise that prevents them from feeling comfortable in their own body (it might have something to do with inflammation and a dysregulated nervous system – both treatable). You know what I’m talking about – root causes.

The type of clinical evaluation I just described actually already exists. There are hundreds of clinics–functional medicine, naturopathic medicine, chiropractic, neurosensorimotor, Ayurvedic, Chinese medicine–all over this country that are interested in root causes instead of pharmaceutical symptom suppression or genetic dismissalism (I just made that word up. I think it fits.)

Looking for such a clinician? Visit the EpidemicAnswers.org practitioner directory to find one near you. There is also a series of clinics called Cortica (in over 20 locations in the U.S.) founded by the brilliant Dr. Susannah Goh who has set up clinics to help parents get to the root causes of their child’s most challenging autism symptoms.

Your Child Is Not Broken

Do not misunderstand me. I did not say that these clinics are here to “fix” your child. Your child is not broken. Autism is a complex condition that brings with it many different types of physiological adaptations, some of which look like health symptoms, some of which look like “neurological differences” and some of which look like talents or gifts.

Many of the features of autism are the body’s way of adapting to particular circumstances, either daily metabolic circumstances (like what food is being eaten, or what microbial metabolites are circulating) or circumstances that occurred during their developmental timeline and created lasting patterns (like echolalia or low muscle tone). Some of these adaptations may be perceived as positive, some may be perceived as negative, and some fall somewhere in the middle.

Eliminating Symptoms That Cause Suffering

Some people with autism are known to have neurological features that could be considered true gifts or remarkable skills such as rapid processing speed, profound artistic ability, or the ability to compute complex numbers effortlessly. The biomedical, root-cause clinics and practitioners that treat children (or now adults) with autism understand that they are there to work on the adaptations that are negative or cause suffering. They are not there to “eliminate autism.” They are there to help the body restore balance and thereby eliminate symptoms that cause suffering. These practitioners will be the first ones to tell you how truly special and amazing the people diagnosed with autism are. They carry struggles, yes, but they also carry gifts, insights and sensitivities rarely seen in neurotypical people.

These clinics are interested in knowing what is going on in the body that might be out of balance and contribute to symptoms that cause suffering (like anxiety, stimming, severe sensory sensitivity, gastrointestinal pain, bloating, skin rashes, inability to control motor function and more).

Shouldn’t we try to alleviate these symptoms? It is considered routine to go to an allergist to look for relief from symptoms of a pollen allergy, but for some reason, we aren’t allowed to look for relief from medical and physical symptoms associated with autism because it bleeds into the territory of identity. That makes no sense. It also prevents people locked inside out-of-balance bodies from getting the medical care and help that they need and deserve.

Please do not see autism as a behavioral diagnosis with a genetic etiology. Autism is a whole-body, medical condition and the “behaviors” are secondary to cells, tissues, networks and functional systems in the body that are, or were, out of balance or dysregulated. Autism is also a unique human presentation that reflects the times we are in – in all its complexity.

People are people, regardless of their diagnosis, and they should have access to “root causes” medicine that is focused on alleviating suffering and stopping problematic symptoms. Kids with autism (or anyone else for that matter) deserve care that addresses the root causes of their troubling symptoms.

What if instead of going to your pediatrician and getting shoulder shrugs and a script for ABA therapy or medications, you went to see a physician trained by MAPS—Medical Academy of Pediatric Special Needs, who asked meaningful, thoughtful questions about what might be contributing to your child’s neurological presentation? What if this doctor had ways to identify addressable imbalances in your child’s body that might alleviate some of their most challenging symptoms?

Here are some of the most common addressable imbalances seen in children with autism and some links with more information about how to help them overcome these imbalances:

For more information on the underlying medical issues seen in autism, see the medical literature linked at the bottom of this article.

Let’s not get caught up in identity politics and whether or not you think people should “treat” autism or look for a “cure” for autism (I never use the word cure, anyway, but that’s another article entirely). Instead, let’s take an objective look at each person’s physiology –regardless of diagnosis–and see if we can identify imbalances and restore balance and function in the body.

Autism Is a Whole-Body Condition

Since autism has a neurological presentation, or looks like “brain symptoms,” people always want to look there first. But brain function is dependent on the health of the cells throughout the whole body, so let’s start there.

While genes play a role, autism is not solely genetic. It is not solely a brain condition. It is a whole-body condition that affects the brain. And just like how heart, liver or kidney function is dependent on the health of the body’s cells, this is also true for the brain.

The human body is designed to self-regulate. Remove the obstacles to healing and the body will find balance and restore function (cognition, digestion, detoxification, nervous system function, immune function, etc.). The body’s default setting is to always move toward healing. This applies for any condition – autoimmune conditions, depression, anxiety, cancer. Any condition.

The Example of Depression

Let’s take a person with depression. If you did an analysis of their gut microbiota to see what microbes and metabolites are present, you will find an imbalance–too many opportunistic and pathogenic microbes, and not enough commensal or helpful microbes. Depression is not just in the head, it’s also in the gut. In people with clinical depression, you will find that they lack microbial diversity and their gut microbiome is often overpopulated with microbes that trigger inflammation (as has been discussed in this paper, and this paper and this paper). Inflammation in the gut means inflammation in the brain.

Instead of prescribing an SSRI, with questionable efficacy data, and documented safety problems, shouldn’t we help that person restore the microbial ecology in their gut to see if it eliminates their symptoms of depression? This has, in fact, been done and is discussed in papers here, here and here. Yet, people still opt for anti-depressant medications with black box warnings over fiber and microbiome therapy.

The Same Gut-Brain Presentation

This same connection between the gut and neurological presentation also exists in autism. People diagnosed with autism are documented to have decreased microbial diversity in their gastrointestinal tracts. Shouldn’t we be treating their microbiomes first? Shouldn’t this be the first line of treatment, instead of 40 hours of ABA?

This type of treatment does happen. All the time. But it is happening on the peripheries of society and isn’t offered at your pediatrician’s office. And it isn’t covered by insurance.

We are kidding ourselves if we don’t acknowledge that our gut microbes are contributing to some of the symptoms of autism. It’s not the whole picture, but it’s a pretty big part of it.

There are stories of moms who changed the diversity of their child’s microbiome through diet, and their child lost their autism diagnosis. Two of my favorite autism and gut healing stories are here and in the video below.

And there are stories of parents who helped their child in other ways beyond diet including detoxification, reduction of oxidative stress, targeted nutritional therapy, and therapies to help overcome missed developmental milestones. Here is a video that tells the stories of four of these families.

We’re Ignoring the Medical Symptoms of Autism

Our society ignores the medical symptoms in people with autism because a false belief emerged at some point that said that the medical symptoms are “just a part of autism.” This includes neurological symptoms that are dismissed because people are told that an autistic brain “works differently.” That is a cop out. It is insulting to tell people with autism that their GI pain is “just a part of autism” or that their sensory overload that makes them anxious and frustrated is due to a brain that “works differently.” People deserve better.

What About Neurological Differences?

Let’s unpack the concept of neurological differences. Neurological differences are good. Neurological differences that also exist in a body that is wracked with inflammation, metabolic syndrome, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular toxicity, severe sensory symptoms, sympathetic nervous system overdrive, adrenal exhaustion, constipation, diarrhea, eczema, and self-injurious behaviors need to be treated very differently. The minute an individual has a medical symptom beyond “neurological difference” we need to treat them medically. And we should consider treating the “neurological difference” if it causes that person suffering.

If you don’t believe me that the “neurological differences” in autism have some basis in whole-body imbalances, talk to a physician who provides functional-lab testing for children with autism. They will tell you. These kids’ bodies are in severe distress. Do you yourself have neurological symptoms? Maybe you should go get some functional-lab testing done. See what comes back. Here’s a menu of tests that you can choose from.

It is imperative that we balance and regulate the body and THEN embrace neurological differences. Do not dismiss neurological differences that are caused by a brain on fire with inflammation. You wouldn’t do this for Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s or depression (all of which are marked by brain inflammation), why do this for autism?

I think the newly emerging neurodiversity narrative, while helpful and supportive in some ways, has the unintended consequence of distracting us away from asking very important questions about why so many more people are experiencing “neurodivergence” in the modern world.

Asking why 1 in 20 children in California has an autism diagnosis, when it was virtually non-existent a few decades ago, is in no way denigrating or diminishing the humanness of anyone who has been diagnosed autism. In fact, it is quite the opposite. The people who are concerned about the escalating rates of autism are concerned about the suffering that they are seeing in those diagnosed with autism, especially the suffering seen in the 40% of people diagnosed as moderate to severe. They are concerned about children diagnosed with severe autism who can’t speak, can’t advocate for themselves, have chronic GI pain, headaches, inflammation and other symptoms that are so severe that they deal with it by banging their heads, acting out, injuring themselves and worse.

Should we celebrate neurodiversity? Yes! Of course!

Should we also ask how we can help support the physical health of the people who are neurodiverse, especially those with symptoms that cause them to suffer? Absolutely.

Can we do both at the same time?

You bet we can.

But first, we have to acknowledge that autism is not just about neurological difference, it is a whole-body condition that carries with it a long list of medical symptoms and conditions that are often overlooked.

Whole-Body Medicine Is Marginalized in Contemporary Medical Culture

This kind of rationalization is understandable in a mechanistic, reductionist Western medical paradigm that treats parts of the body as distinct, separate and not integrated. Sure, this rationalization makes sense if you are still captured by the idea of genetic determinism, that is, that conditions like autism (for which they don’t have other explanations) are probably caused by genetics. Traditional medicine (e.g., traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, ancestral and indigenous forms of medicine) see the body as an integrated whole, and if the bowel is inflamed, so is the brain. Here is an Ayurvedic description of autism published in The Journal of Ayurveda and Integrated Medical Sciences, Feb 2023:

Ayurveda understands the nature of human brain in a completely different manner from modern psychiatric and physiological theories. Autism has close similarities to the features of that Unmada which is described in Ayurveda. The condition may be due to Khavaigunya (disrrangements) of Srotas (channels) which nurtures Manas (mind) as a consequence of many Agantuja (epigenetic and toxic insults and post-natal environmental factor) and Sahaja (genetic) factors.

These traditional medical paradigms understand what is causing autism and why we are seeing so many more children being diagnosed with autism, yet this way of thinking is really marginalized in contemporary medical culture. This is changing with the rise of integrative, functional, holistic medicine and as ancient and indigenous forms of medicine are becoming more widely accepted. Sadly, it is not changing fast enough.

While you may not understand the terms like Srotas or Agantuja, the Ayurvedic perspective is that environmental factors (pre-conception, prenatal, neonatal and current) have impacted, and are impacting the body’s ability to “think clearly” or “think typically.” This perspective (along with other holistic approaches) also recognizes that all the organs and systems in the body are one; everything is connected.

If you have pain or disruption in one area of the body, you better believe this will affect other areas of the body. If there are severe headaches, and inflammation in the bowel, or chronic constipation or diarrhea, then something in the body is out of balance, and the brain’s “way of thinking” is going to be impacted. Period. The gut and brain are intricately linked. If there is anxiety or depression, then the microbiome is out of balance.

Yet, we are still sticking to the story that autism is just ‘neurodivergence’ and we shouldn’t treat the root causes of the “accompanying” medical conditions. That chronic burning diarrhea is just “a part of autism” and has nothing to do with “neurological difference.”

Are you sure you want to die on that hill?

Because what if we healed the problems in the gut? Maybe that would positively impact the brain and allow that individual to “think differently” but without the buzz, the noise, the sensory overload, or the pain.

Parkinson’s affects the way people’s brains work and the way people think, so does depression, and bipolar disorder. But we don’t call people with those conditions neurodivergent. We are seeing skyrocketing rates of conditions that affect the brain, whether you call it neurodivergence, neurodegeneration or mental health or neurological conditions.

What all these conditions have in common is inflammation and toxicity in the brain.

Documented Cases of Full Reversal of Neurodivergent Conditions

What’s more, there is a growing body of scientific and medical literature documenting cases of full reversal of autism, ADHD and other “neurodivergent” conditions by addressing inflammation, toxicity, and neurological dysregulation.

Let me state that a different way. Science is now demonstrating that the features of neurodivergence may actually be secondary to environmental, metabolic and other phenomenon and are documenting cases of people who lost their neurodivergence and autism diagnosis by modifying things in the environment, reducing inflammation and toxic load, and supporting the body with health and life-supporting activities (nutrition, natural sunlight, sleep, movement-based therapeutics and more).

Here are some examples:

- O’Hara N.H., Szakacs, G.M. The recovery of a child with autism spectrum disorder through biomedical interventions. Altern Ther Health Med. 2008;14(6):42-4.

- Baker, S., et al. Case Study: Rapid Complete Recovery From An Autism Spectrum Disorder After Treatment of Aspergillus With The Antifungal Drugs Itraconazole And Sporanox. Integr Med (Encenitas). 2020 Aug;19(4):20-27.

- Fein, D., et al.: Optimal Outcomes in Individuals with a History of Autism. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 2013.

People who have lost their autism diagnoses through root-cause-oriented biomedical treatment are a “fly in the ointment” of the old guard medical establishment that are still convinced that autism is mainly genetic and unchangeable.

I’ve also been documenting this phenomenon for 15 years and have been listening to the stories of the people that have lost their autism diagnoses. Why are we marginalizing these people and dismissing their stories? Shouldn’t we be running to them and asking, “what did you do?” In my opinion, their stories are sacred.

What are we afraid of?

If there are many cases of children who once met the criteria for moderate to severe autism but after they addressed things like inflammation, infections, toxicity, nutrition, nervous system regulation and sensory integration, they no longer met the criteria for autism, and they were no longer “neurodivergent,” then what is autism, really?

The Biomedical Definition of Autism

Autism spectrum disorder is a multi-system developmental disorder caused by an accumulation of environmental stressors impacting genetically susceptible individuals during critical developmental moments.

Remember what I said about how the body always prioritizes survival over development. What happens to a baby that is born prematurely, who comes into this world already loaded with a bucket full of toxins in their tiny body (over 280 synthetic chemicals in cord blood according to EWG), whose nervous system is on overdrive with the fluorescent lights and other sights, smells and sounds of the NICU, who was exposed to antibiotics because his mother tested positive for group B strep during pregnancy, who then had a hepatitis B vaccine at one week old, who then couldn’t breastfeed due to latching issues and his mother’s painful thrush infection on her nipples (caused by her imbalanced microbiome), who then went home to a house filled with everyday American life products that are synthetic, endocrine disrupting, and toxic to human cells and slept every night on an infant bassinet mattress made of PVC and flame retardants?

That baby is supposed to channel his energy into developing vision, hearing, speech, social communication, motor development and more. But his little body is just too overloaded and prioritizes detoxification, repairing DNA damage, and dealing with the toxic microbial metabolites churning out of his altered gut microbiome. This baby doesn’t have any energy left to do the normal developmental work. Just like a bridge that collapses after years of heavy trucks crossing it, the body collapses into autism as the multiple triggers add up. Depending upon the triggers, the timing, and the heritable differences (genetics and inherited microbiome), different systems are affected in each individual related to his/her bioindividuality.

More often than not, we don’t pick up this child’s developmental issues until they are very far down the line. Maybe the child is 3 or 4 or 5 years old. . . when he is supposed to be speaking, walking, writing, jumping. But he isn’t. So, he gets an autism diagnosis. And we tell the parents that he was “born this way,” and “he will always be this way” and there is nothing you can do but support him with ABA to help him pick up the spoon and fork and to force him to look you in the eye.

Even. Though. He. Can’t.

What are we doing to these children?

Neuroplasticity

Thanks to discoveries around neuroplasticity, you can change the “hardwiring,” so even if your brain experienced stress, toxicity, and inflammation during critical developmental times and “wired” your brain in a particular way, there are dozens of ways to leverage neuroplasticity to overcome the challenges.

Also, while I used the word “hardwiring”, maybe we should think of the brain “thinking differently” as a fluid and adaptive response rather than a hardwiring. In other words, the brain adapted to a circumstance (inflammation, stress, chemicals, infection, cellular toxicity) and created certain neural networks as an adaptation to get around or deal with the dysfunction or dysregulation created by the environmental stressors. This adaptation doesn’t have to always be a negative experience like not knowing how to socialize in a social world. It could be a wonderful adaptation that created the ability to see or hear things that are outside the “typical” human range or perhaps to be able to process abstract concepts beyond what is typical.

Changing the hardwiring isn’t necessarily what neurodivergent people or people with autism need. They may want or need that, but at a minimum, they certainly need their medical conditions and physiological imbalances treated.

Why Are We Ignoring the Medical Issues?

So, why are we ignoring neurodivergent people’s medical issues and physiological imbalances? Why aren’t we offering treatment?

- Because it can be hard;

- Because it can be expensive and isn’t covered by insurance;

- Because by doing so we must acknowledge all the things in our culture and daily lives that are hurting our children. We must acknowledge that we (our society) are responsible for the autism epidemic. And no one wants to shoulder that shame or guilt.

Go ahead and Google: “Why do so many people have autism today?” Let me know what you get. You probably won’t get a clear answer, if you get an answer at all.

More likely than not, most articles like this one, from the captured media NBC News, will tell you—definitively—that they don’t know what causes autism, although it’s probably genetic with maybe just a touch of environmental factors. Just a smidge. A sprinkling, really. But it’s mostly genetic, and they will also tell you—definitively–what does not cause autism. Vaccines do not cause autism.

Okey dokey.

Why Is No One Asking What Causes Autism?

Why won’t anyone ask the question, what causes autism?

It isn’t because “science” doesn’t know. Science does know. There are thousands of physicians and scientists doing amazing work that have uncovered a profound, deep and rich understanding of what happens in a child’s body during critical developmental times (in utero, neonatal, and during the first few years of life) that contributes to the syndrome of symptoms that we label as autism.

The scientists know! They just aren’t allowed to talk about it in polite society because the answer is too painful for us as compassionate, caring, human beings and as a society. It hurts too much. It hurts to know that we (society, parents, pediatricians, culture) unwittingly contributed to a condition that we don’t understand and causes suffering in many.

Notice I used the word unwittingly.

We. Had. No. Idea.

We had no idea that living in the modern world (using toxic chemical products, living stressed-out crazy lives, taking synthetic pharmaceuticals that poison your cells, disrupt your hormones, wipe out your microbiome) would impact our children’s development.

We didn’t know.

And so, we bury our heads in the sand. Meanwhile, thousands of courageous parents who know what caused their child’s autism and work every day to try and help support their child the best way they know how feel abandoned by a medical system that doesn’t listen to them, dismisses them, and labels them with terms of hate speech like “anti-vaxxer” or belittling terms like “paranoid helicopter mother” or some other middle-school level deflection.

“How Can We Help You Be Your Best Self?”

I’m afraid that by emphasizing the need to celebrate neurodiversity without also simultaneously acknowledging the things that contributed to the neurodivergence isn’t the best way to help our neurodivergent friends, family and children thrive. By telling them their symptoms (even the ones that don’t have anything to do with “thinking differently”) are just a “part of their autism,” we are denying them the possibility of living their best life, of growing to be the best version of themselves. Maybe we are thrusting our limiting beliefs on these children because we are afraid to face the truth of what we have done. Or a more likely interpretation is that we just didn’t know. And that is eminently forgivable.

Instead of just saying “we accept you just as you are because you are neurodivergent,” what if we said, “how can we help you feel and be the best version of yourself so you could be neurologically who you are but without the struggles, without the pain, without the challenges?”

What are we to make of the people (adults and children) who have lost their autism diagnosis? Those who were diagnosed with severe autism, nonspeaking, self-injurious and then changed their diet and followed a holistic and therapeutic path . . . who no longer have any symptoms of autism . . . What is the identity of that individual?

You Are Not Your Diagnosis

Identity. Noun. the distinguishing character or personality of an individual

You are not autism. Autism is not you. Autism is a part of you, it is a part of your experience, it has shaped and defined you in so many ways, good and bad. And while you may no longer fit the diagnostic criteria for autism, no one can take your experience with autism away. But autism does not define who you are. You are you with or without autism.

Autism is a word used to label you because people don’t understand you. Because people feel like they need to make excuses, explanations, or rationales for why you are the way you are. Why can’t they instead try to listen to you or observe you? To ask you, “What are your struggles?” “How can I help you overcome the challenges you face?” You can’t overcome the challenges you face as a child with autism in a medical system that only offers you synthetic petrochemical pharmaceuticals that only mask symptoms and don’t address the root causes.

What if someone said to you: I can help you understand the root causes of the symptoms that bother you. If autism is your identity, or your “distinguishing character or personality” that is fine, but don’t let them tell you that is all you are. You are so much more.

This is true for ANYONE, not just people who are neurodivergent or neurodiverse. Your symptoms do not define you.

A “neurotypical” person who has symptoms of anxiety might consider themselves “anxious” by nature, but they do not have to be debilitated by that anxiety, nor do they have to suffer from that anxiety just because someone gave them that label. And they certainly don’t need to be on synthetic pharmaceutical drugs for their entire life because someone gave them the diagnosis or label of “anxiety.” There are whole-body, health-supporting treatments for anxiety. They just aren’t on the shelf at CVS. And they take some work.

In 2024, there are many ways to reverse and eliminate symptoms of anxiety that don’t require taking pharmaceuticals. Eliminating your anxiety does not change who you are; it simply allows you to be a better, happier version of yourself where you are not inhibited or held back by your anxiety.

As a society, we must not dismiss truly serious health and medical symptoms that are addressable, actionable, and often times reversible just because someone is “neurodivergent,” and we must provide resources for parents who want to help their children heal.

Healing Is Not a Rejection of Who a Child Is

Not accepting that your child’s diagnosis is a lifelong and intractable condition is not the same as rejecting your child or rejecting who they are. The child/human/soul that is inside that body wants their body to cooperate, to be in sync, to be toxin-free, nourished and healthy. If you want that, too, please know that there is an entire community of people that feel the same way you do, that want to help you, and are working to heal their children, too.

I know. It feels really, really hard. Near impossible.

How will I pay for the therapies?

How will I get him to eat?

How will I find the time to learn all the things I need to learn?

How will I know what is toxic and what is safe?

How do I change the microbiome?

You will find a way.

You can do hard things. Your child chose you because they know that you are strong and capable and loving and determined. And it’s okay to ask for help and support.

Resources for Healing

I created Epidemic Answers and Documenting Hope to help you. My colleagues and I built a library of resources. We built a provider directory and trained health coaches. We built a community of parents just like you, learning how to heal their children, together.

At the end of the day, it’s up to you.

You get to decide whether to embark on this healing journey or not. There is no judgement for any path you choose.

Maybe you think you don’t have what it takes to guide them. Let me tell you something. You do. You definitely do.

James’ Story

For the parents who have a child with autism who is a nonspeaker or unreliable speaker, I would like to share something special with you.

This is a story written by a young man with autism named James. James does not have the ability to produce reliable speech. James learned how to communicate using a method called RPM where a facilitator helps him communicate via a letterboard. You may be familiar with another similar method called S2C or Spelling to Communicate. This method was the focus of a recent documentary film called Spellers. I highly encourage you to watch it. It will change your mind about autism, forever.

Here is a story told by James:

ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS AN UNUSUAL BOY WHO COULD NOT TALK. HE WAS VERY LONELY. HE LIVED IN A TOWER OF SILENCE. THE BOY WAS ALWAYS THINKING. HE THOUGHT ABOUT ALL THE THINGS HE HEARD DURING THE COURSE OF HIS LIFE. THE BOY HAD NOTHING BUT TIME TO CONTEMPLATE LIFE AND PEOPLE IN IT. THEN ONE DAY HE WAS INTRODUCED TO A POWERFUL WIZARD WHO GAVE HIM A MAGICAL BOARD THAT TRANSLATED HIS THOUGHTS INTO WORDS! THE BOY WAS ECSTATIC! HE WAS NOW ABLE TO COMMUNICATE ALL HIS THOUGHTS. AFTER THE BOY STARTED USING THE MAGICAL BOARD HIS ENTIRE LIFE CHANGED. PEOPLE STARTED TREATING THE BOY VERY DIFFERENTLY. THEY WERE SHOCKED BY HOW MUCH THE BOY KNEW AND THAT HE WAS CAPABLE OF LEARNING AT ALL! THE BOY KNEW THAT HE HAD TO HONOR THE GIFT OF THE MAGICAL BOARD. HE MUST USE THE BOARD TO TEACH THE WORLD ABOUT OTHERS WHO ARE STUCK IN THEIR OWN WORLDS OF SILENCE.

THE BOY WAS ALREADY FAMILIAR WITH THE PERCEPTIONS OF PEOPLE ABOUT HOW THOSE WHO DO NOT SPEAK. HE HAD TO BLAZE A NEW TRAIL FOR THE OTHER SILENT PEOPLE. HE HAD TO SHOW THAT SILENT DOES NOT EQUAL STUPID. THE BOY KNEW THE BEST WAY TO LEAD WAS THROUGH EXAMPLE. HE USED THE MAGICAL BOARD TO SHARE HIS WORDS WITH THE WORLD. THE BOY WAS ADORED BY ALL AND SLOWLY LED THE SILENT PEOPLE INTO THE WORLD!

James’ mother believed in his ability to communicate—even if he was not able to reliably speak. So, she found a way. She was a pioneer. She was among the first to bring RPM to the United States and to the families who desperately wanted to unlock the thoughts inside the heads of their nonspeaking children. And it changed everything.

Without the advocacy and guiding light of his mother, James would have been considered “intellectually disabled” and left locked inside his body with no ability to communicate. Instead, he was given the opportunity to communicate, attend college and share his brilliant intellect with the world. Because someone believed in him. You can read more from the brilliant and talented James here.

James’s mother was told all kinds of things about what James couldn’t do or be.

She didn’t listen. She believed in James and kept looking for answers.

Here’s what James, his mother, and others like them came to teach us:

Believe in your child.

Believe that your child is doing the best he can with the dysregulated body he is inhabiting.

Believe in your child’s ability to heal.

Believe in the gifts and wisdom that your child brings to this world.

Believe that your child is competent, capable, intelligent.

Believe that there is more for him. There is always more.

And finally, know that your child is here to teach you something. They are here to teach us all something.

I have not met one parent of a recovered child or a child who made incredible healing strides who did not say that their child was their teacher.

Not one.

My Personal Viewpoint

I have a personal viewpoint on what I think autism is, really.

And like James, I’ll tell it as a story.

Once upon a time, there was a little blue-and-green planet. This planet was teeming with life, lush forests, abundant prairies, crystal-clear lakes and endless miles of majestic oceans. For many years, this planet hosted a complex and intelligent people that could create anything they wanted through consciousness and individual and collective action. For many years, these beautiful creatures lived in relative harmony with this planet. One of the distinguishing characteristics of these people was their ability to develop tools or create new technologies. Slowly, over time, this clever little species developed more and more tools that gave it more control over its natural environment. No longer did these people have to live out in the cold or be subject to the whims of unpredictable weather. Food could be created rather than grown or harvested. Homes could be built sturdy and resilient to keep out pests and predators. These people created medicines and chemicals to kill microbes believed to sicken them.

In its eagerness to do good, to make life cleaner, easier, safer—these people had mistaken powerful agents of destruction for solutions to their problems. What these people did not know is that while some of them would become affluent, resourced and scientifically advanced, the consequence for this “advancement” would be a poisoned planet and sick and dying species, including their own. The people had poisoned the lakes, rivers and oceans. They polluted the skies and the soils. They destroyed the diversity of species and filled the landscape with synthetic and chemical garbage that would take thousands of years to decompose. The people’s destructive relationship to their environment was having a devastating impact on their health, yet they were not able to see the connection. They continued to use their technologies and their advancements to solve for their health problems. And they got sicker and sicker. All the while, the answer was right in front of their faces. By disconnecting from nature, they unwittingly disconnected from themselves.

This little planet sent the children as messengers. They were sent to reflect for us that which we do not yet understand about our own divinity, about our own need to live with and through nature, instead of controlling, exploiting or being separate from it. These children arrived with unprecedented gifts and perceptive abilities to teach us about the fundamental nature of human existence, about our natural gifts and capabilities that have been long forgotten. They were sent here to remind us of what it means to be human. To feel and perceive things intensely. To communicate with ALL of our capacity, not just our words. To know how to shut out the outside world, truly go inwards, and be in the experience of presence.

While many of these children cannot speak, their communication to us could not be any clearer.

The question is, are we listening?

So, what do you think autism is, really?

About Beth Lambert

Beth Lambert is a former healthcare consultant and teacher. As a consultant, she worked with pharmaceutical, medical device, diagnostic and other health care companies to evaluate industry trends.

She is the author of A Compromised Generation: The Epidemic of Chronic Illness in America’s Children (Sentient Publications, 2010). She is also a co-author of Epidemic Answers’ Brain Under Attack: A Resource for Parents and Caregivers of Children with PANS, PANDAS, and Autoimmune Encephalitis.

In 2009, Beth founded Epidemic Answers and currently serves as Executive Director. Beth attended Oxford University and graduated from Williams College and holds a Masters Degree in American Studies from Fairfield University.

Still Looking for Answers?

Visit the Epidemic Answers Practitioner Directory to find a practitioner near you.

Join us inside our online membership community for parents, Healing Together, where you’ll find even more healing resources, expert guidance, and a community to support you every step of your child’s healing journey.

Sources & References

Accardo, P.J., et al. Toe walking in autism: further observations. J Child Neurol. 2015 Apr;30(5):606-9.

Adams, J.B., et al. Comprehensive Nutritional and Dietary Intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder-A Randomized, Controlled 12-Month Trial. Nutrients. 2018 Mar 17;10(3).

Adams, J.B., et al. Effect of a vitamin/mineral supplement on children and adults with autism. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:111.

Adams, J.B., et al. Mercury in first-cut baby hair of children with autism versus typically-developing children. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry. 2007 Jun;70(12):1046-51.

Adams, J.B., et al. Mercury, Lead, and Zinc in Baby Teeth of Children with Autism Versus Controls. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 2007 Jun;70(12):1046-51.

Adams, J.B., et al. Nutritional and metabolic status of children with autism vs. neurotypical children, and the association with autism severity. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011 Jun 8;8(1):34.

Adams, J.B., et al. Vitamin/mineral/micronutrient supplement for autism spectrum disorders: a research survey. BMC Pediatr. 2022 Oct 13;22(1):590.

Alabdali, A., et al. A key role for an impaired detoxification mechanism in the etiology and severity of autism spectrum disorders. Behav Brain Funct. 2014;10:14.

Alabdali, A., et al. Association of social and cognitive impairment and biomarkers in autism spectrum disorders. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:4.

Aldad, T.S., et al. Fetal Radiofrequency Radiation Exposure From 800-1900 Mhz-Rated Cellular Telephones Affects Neurodevelopment and Behavior in Mice. Sci Rep. 2012;2:312.

Ashraghi, R.S., et al. Early Disruption of the Microbiome Leading to Decreased Antioxidant Capacity and Epigenetic Changes: Implications for the Rise in Autism. Front. Cell. Neurosci., 15 Aug 2018.

Ashwood, P., et al. Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav Immun. 2011 Jan;25(1):40-5.

Ashwood, P., et al. The immune response in autism: a new frontier for autism research. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2006 Jul;80(1):1-15.

Atladóttir, H.Ó., et al. Association of family history of autoimmune diseases and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2009 Aug;124(2):687-94.

Atladóttir, H.Ó., et al. Autism after infection, febrile episodes, and antibiotic use during pregnancy: an exploratory study. Pediatrics. 2012 Dec;130(6):e1447-54.

Baker, S. Canaries and Miners. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. Nov-Dec 2008;14(6):24-6.

Baker, S., et al. Case Study: Rapid Complete Recovery From An Autism Spectrum Disorder After Treatment of Aspergillus With The Antifungal Drugs Itraconazole And Sporanox. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2020 Aug;19(4):20-27.

Barrett, B. Substantial lifelong cost of autism spectrum disorder. J Pediatr. 2014;165(5):1068-9.

Bateman, C. Autism–mitigating a global epidemic. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(5):276-7.

Bernard, S., et al. Autism: a novel form of mercury poisoning. Med Hypotheses. 2001 Apr;56(4):462-71.

Binder, D.K., et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Factors. 2004 Sep;22(3):123-31.

Bittker, S.S., et al. Postnatal Acetaminophen and Potential Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder among Males. Behav Sci (Basel). 2020 Jan 1;10(1):26.

Bitsika, V., et al. Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis daily fluctuation, anxiety and age interact to predict cortisol concentrations in boys with an autism spectrum disorder. Physiol Behav. 2015;138:200-7.

Bjørklund, G., et al. Gastrointestinal alterations in autism spectrum disorder: What do we know? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020 Nov:118:111-120.

Blaxill, Mark, et al. Autism Tsunami: the Impact of Rising Prevalence on the Societal Cost of Autism in the United States. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022 Jun;52(6):2627-2643.

Blaylock, R.L. A possible central mechanism in autism spectrum disorders, part 1. Altern Ther Health Med. 2008 Nov-Dec;14(6):46-53.

Blaylock, R.L. A possible central mechanism in autism spectrum disorders, part 2: immunoexcitotoxicity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009 Jan-Feb;15(1):60-7.

Blaylock, R.L. A possible central mechanism in autism spectrum disorders, part 3: the role of excitotoxin food additives and the synergistic effects of other environmental toxins. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009 Mar-Apr;15(2):56-60.

Blaylock, R.L., et al. Immune-glutamatergic dysfunction as a central mechanism of the autism spectrum disorders. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(2):157-70.

Boat, T.F., et al. Prevalence of Learning Disabilities. Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015 Oct 28. 16.

Borre, Y.E., et al. Microbiota and neurodevelopmental windows: implications for brain disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2014 Sep;20(9):509-18.

Bradstreet, et al. Biomarker-guided interventions of clinically relevant conditions associated with autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Altern Med Rev. 2010;15(1):15-32.

Bransfield, R.C., et al. The association between tick-borne infections, Lyme borreliosis and autism spectrum disorders. Medical Hypotheses. 2008;70(5):967-74.

Breitenkamp, A.F., et al. Voltage-gated Calcium Channels and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2015;8(2):123-32.

Brown, et al. Observable essential fatty acid deficiency markers and autism spectrum disorder. Breastfeed Rev. 2014;22(2):21-6.

Buescher, et al. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):721-8.

Buie, T., et al. Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in individuals with ASDs: a consensus report. Pediatrics. 2010 Jan;125 Suppl 1:S1-18.

Buie, T., et al. Recommendations for evaluation and treatment of common gastrointestinal problems in children with ASDs. Pediatrics. 2010 Jan;125 Suppl 1:S19-29.

Bull, G., et al. Indolyl-3-acryloylglycine (IAG) is a putative diagnostic urinary marker for autism spectrum disorders. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(10):CR422-5.

Büsselberg, D. Calcium channels as target sites of heavy metals. Toxicol Lett. 1995 Dec:82-83:255-61.

Camilleri, M. Serotonin in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Endrocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009 Feb;16(1):53-9.

Carlo, G.L., et al. Wireless radiation in the aetiology and treatment of autism: clinical observations and mechanisms. Journal of the Australasian College of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine, 26(2), 3–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. Accessed 24 Mar 2023.

Cheng, N., et al. Metabolic Dysfunction Underlying Autism Spectrum Disorder and Potential Treatment Approaches. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017 Feb 21:10:34.

Clarke, E.B., et al. Understanding profound autism: implications for stigma and supports.

Front Psychiatry. 2024 Jan 22:15:1287096.

Connolly, A.M., et al. Serum autoantibodies to brain in Landau-Kleffner variant, autism, and other neurologic disorders. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1999 May;134(5):607-13.

Critchfield, et al. The potential role of probiotics in the management of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:161358.

Cubala-Kucharska M. The review of most frequently occurring medical disorders related to aetiology of autism and the methods of treatment. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 2010;70(2):141-6.

Currenti, S.A. Understanding and determining the etiology of autism. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010 Mar;30(2):161-71.

Dale, R.C., et al. Encephalitis lethargica syndrome: 20 new cases and evidence of basal ganglia autoimmunity. Brain. 2004 Jan;127(Pt 1):21-33.

Darling, A.L., et al. Association between maternal vitamin D status in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood: results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Br J Nutr. 2017 Jun;117(12):1682-1692.

Dasdaq, S., et al. Effects of 2.4 GHz radiofrequency radiation emitted from Wi-Fi equipment on microRNA expression in brain tissue. Int J Radiat Biol. 2015 Jul;91(7):555-61.

Dave, D., et al. The effect of an increase in autism prevalence on the demand for auxiliary healthcare workers : evidence from California. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012. 37 p.p.

D’Eufemia, P., et al. Abnormal intestinal permeability in children with autism. Acta Paediatr. 1996 Sep;85(9):1076-9.

Deisher, T.A., et al. Impact of environmental factors on the prevalence of autistic disorder after 1979. J Public Health and Epidemiology. Sep 2014;6(9):271-286.

de Magistris, L., et al. Alterations of the intestinal barrier in patients with autism spectrum disorders and in their first-degree relatives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(4):418-24.

Deth, R., et al. How environmental and genetic factors combine to cause autism: A redox/methylation hypothesis. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29(1):190-201.

Dyńka, D., et al. The Role of Ketogenic Diet in the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Nutrients. 2022 Nov 24;14(23):5003.

Elamin, N.E., et al. Brain autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorder. Biomark Med. 2014;8(3):345-52.

El-Ansary, A., et al. Neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorders. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:265.

El-Ansary, A., et al. Lipid mediators in plasma of autism spectrum disorders. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:160.

Egset, K., et al. Magno App: Exploring Visual Processing in Adults with High and Low Reading Competence. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 07 Jan 2020.

Erickson, C.A., et al. Gastrointestinal Factors in Autistic Disorder: A Critical Review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005 Dec;35(6):713-27.

Faber, S., et al. A cleanroom sleeping environment’s impact on markers of oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, and behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:71.

Fattorusso, A., et al. Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2019 Feb 28;11(3):521.

Fein, D., et al. Optimal outcome in individuals with a history of autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013 Feb;54(2):195-205.

Frustaci, A., et al. Oxidative stress-related biomarkers in autism: systematic review and meta-analyses. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(10):2128-41.

Frye, R.E., et al. Redox metabolism abnormalities in autistic children associated with mitochondrial disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e273.

Frye, R.E., et al. Metabolic pathology of autism in relation to redox metabolism. Biomark Med. 2014;8(3):321-30

Gadow, K.D., et al. Association of COMT (Val158Met) and BDNF (Val66Met) gene polymorphisms with anxiety, ADHD and tics in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(11):1542-51.

Gadow, K.D., et al. Association of DRD4 polymorphism with severity of oppositional defiant disorder, separation anxiety disorder and repetitive behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32(6):1058-65.

Gebril, O.H., et al. HFE gene polymorphisms and the risk for autism in Egyptian children and impact on the effect of oxidative stress. Dis Markers. 2011;31(5):289-94.

Geier, D.A., et al. The biological basis of autism spectrum disorders: Understanding causation and treatment by clinical geneticists. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 2010;70(2):209-26.

Ghanizadeh, A. Increased glutamate and homocysteine and decreased glutamine levels in autism: a review and strategies for future studies of amino acids in autism. Dis Markers. 2013;35(5):281-6

Goldani, A.A., et al. Biomarkers in autism. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:100

Goncalves, M.V.M., et al. Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) misdiagnosed as autism spectrum disorder. Immunol Lett. 2018 Nov;203:52-53.

Gough, S., et al. Neuroprotection by the Ketogenic Diet: Evidence and Controversies. Front Nutr. 2021 Nov 23:8:782657.

Grandjean, P., et al. Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet. 2006 Dec 16;368(9553):2167-78.

Grimaldi, R., et al. A prebiotic intervention study in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Microbiome. 2018 Aug 2;6(1):133.

Guilford, T., et al. Deficient Glutathione in the Pathophysiology of Mycotoxin-Related Illness. Toxins (Basel). 2014 Feb 10;6(2):608-23.

Guyol, G. Who’s crazy here?: Steps for recovery without drugs for: ADD/ADHD, addiction & eating disorders, anxiety & PTSD, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, autism. 1st U.S. ed. Stonington, CT: Ajoite Pub.; 2010. 123 p.p.

Hacohen, Y., et al. N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate (NMDA) receptor antibodies encephalitis mimicking an autistic regression. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016 Oct;58(10):1092-4.

Hallmayer, J., et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Nov;68(11):1095-102.

Hamad, A.F., et al. Prenatal antibiotics exposure and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2019 Aug 29;14(8):e0221921.

Hejitz, R.D., et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Feb 15;108(7):3047-52.

Herbert, M.R., et al. Autism and Dietary Therapy: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Child. Neurol. 2013;28:975–982.

Herbert, M.R., et al. Autism and environmental genomics. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27(5):671-84.

Herbert, M.R, et al. Autism and EMF? Plausibility of a pathophysiological link–Part I. Pathophysiology 20.3 (2013): 191-209.

Herbert, M.R., et al. Autism and EMF? Plausibility of a pathophysiological link Part II. Pathophysiology 20.3 (2013): 211-234.

Herbert, M.R. Contributions of the environment and environmentally vulnerable physiology to autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010 Apr;23(2):103-10.

Hertz-Picciotto, I., et al. The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology. 2009 Jan;20(1):84-90.

Hertz-Picciotto, I., et al. Organophosphate exposures during pregnancy and child neurodevelopment: Recommendations for essential policy reforms. PLoS Med. 2018 Oct 24;15(10):e1002671.

Hertz-Picciotto, I., et al. Prenatal exposures to persistent and non-persistent organic compounds and effects on immune system development. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008 Feb;102(2):146-54.

Heyer, N.J., et al. Disordered porphyrin metabolism: a potential biological marker for autism risk assessment. Autism Res. 2012;5(2):84-92.

Holmes, A., et al. Reduced Levels of Mercury in First Baby Haircuts of Autistic Children. International Journal of Toxicology. Jul-Aug 2003;22(4):277-85.

Horvath, K., et al. Autistic disorder and gastrointestinal disease. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2002 Oct;14(5):583-7.

Horvath, K., et al. Gastrointestinal abnormalities in children with autistic disorder. Journal of Pediatrics. 1999 Nov;135(5):559-63.

Howsmon, D. P., et al. Multivariate techniques enable a biochemical classification of children with autism spectrum disorder versus typically‐developing peers: A comparison and validation study. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine. 2018. doi:10.1002/btm2.10095.

Hyman, M. Autism: Is It All in the Head? Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. Nov-Dec 2008;14(6):12-5.

Isaksson, J., et al. Brief Report: Association Between Autism Spectrum Disorder, Gastrointestinal Problems and Perinatal Risk Factors Within Sibling Pairs. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017 Aug;47(8):2621-2627.

Ivanovski, I., et al. Aluminum in brain tissue in autism. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2019 Jan;51:138-140.

Jafari, M.H., et al. The Relationship Between the Level of Copper, Lead, Mercury and Autism Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 21 Sep 2020(11):369—378.

James, S.J., et al. Metabolic biomarkers of increased oxidative stress and impaired methylation capacity in children with autism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6):1611-7.

Jarusiewicz, B. Efficacy of Neurofeedback for Children in the Autistic Spectrum: A Pilot Study. Journal of Neurotherapy. 2002;6(4).

Jyonouchi, H., et al. Dysregulated innate immune responses in young children with autism spectrum disorders: their relationship to gastrointestinal symptoms and dietary intervention. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;51(2):77-85.

Jyonouchi, H., et al. Impact of innate immunity in a subset of children with autism spectrum disorders: a case control study. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2008 Nov 21;5:52.

Kaluzna-Czaplinska, J., et al. Identification of organic acids as potential biomarkers in the urine of autistic children using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2014;966:70-6.

Kane, R.C. A possible association between fetal/neonatal exposure to radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation and the increased incidence of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Med Hypotheses. 2004;62(2):195-7.

Kang, D.W., et al. Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome. 2017 Jan 23;5(1):10.

Kang, D.W., et al. Long-term benefit of Microbiota Transfer Therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Scientific Reports. 9, 5821 (2019).

Karhu, E., et al. Nutritional interventions for autism spectrum disorder. Nutr Rev. 2020 Jul 1;78(7):515-531.

Kern, J.K., et al. A biomarker of mercury body-burden correlated with diagnostic domain specific clinical symptoms of autism spectrum disorder. Biometals. 2010;23(6):1043-51.

Khan, Z., et al. Slow CCL2-dependent translocation of biopersistent particles from muscle to brain. BMC Med. 2013 Apr 4;11:99.

Konstantareas, M.M., et al. Ear infections in autistic and normal children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1987 Dec;17(4):585-94.

Kordulewska, N.K., et al. Serum cytokine levels in children with spectrum autism disorder: Differences in pro- and anti-inflammatory balance. J Neuroimmunol. 2019 Dec 15;337:577066.

Kushak, R.I., et al. Intestinal Disaccharidase Activity in Patients with Autism: Effect of Age, Gender, and Intestinal Inflammation. Autism. 2011;15:285–294.

Kuwabara, H., et al. Altered metabolites in the plasma of autism spectrum disorder: a capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectroscopy study. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73814.

Lai, C.C.W., et al. The association between gut-health promoting diet and depression: A mediation analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023 Mar 1:324:136-142.

Lathe, R. Environmental factors and limbic vulnerability in childhood autism; Clinical report. American Journal of Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 4 (2): 183-197, 2008.

Lathe, R. Microwave Electromagnetic Radiation and Autism. E-Journal of Applied Psychology. June 2009;5(1):11-30.

Lavelle, T.A., et al. Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e520-9.

Lee, K., et al. Autism-associated Shank3 mutations alter mGluR expression and mGluR-dependent but not NMDA receptor-dependent long-term depression. Synapse. 2019 Aug;73(8):e22097.

Lee, R.W.Y., et al. A modified ketogenic gluten-free diet with MCT improves behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Physiol Behav. 2018 May 1:188:205-211.

Li, Q., et al. A Ketogenic Diet and the Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Pediatr. 2021 May 11:9:650624.

Li, Q., et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children and Adolescents in the United States From 2019 to 2020. JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Sep 1;176(9):943-945.

Li, S.O., et al. Serum copper and zinc levels in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Neuroreport. 2014;25(15):1216-20.

Li, Y., et al. Association between MTHFR C677T/A1298C and susceptibility to autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. BMC Pediatrics. 2020(20)449.

Liao, T.C., et al. Comorbidity of Atopic Disorders with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Pediatr. 2016 Apr;171:248-55.

Postnatal immune activation causes social deficits in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis: Role of microglia and clinical implications. Sci Adv. 2021 Sep 17;7(38):eabf2073.

Madra, M., et al. Gastrointestinal Issues and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2021 Mar; 44(1): 69–81.

Maenner, M.J., et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years – Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021 Dec 3;70(11):1-16.

Maher, P. Methylglyoxal, advanced glycation end products and autism: is there a connection? Med Hypotheses. 2012;78(4):548-52.

Melke, J., et al. Abnormal melatonin synthesis in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;13(1):90-8.

Mierau, S.B., et al. Metabolic interventions in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurobiol Dis. 2019 Dec:132:104544.

Mold, M., et al. Aluminium in brain tissue in autism. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2018 Mar;46:76-82.

Mu, C., et al. Metabolic Framework for the Improvement of Autism Spectrum Disorders by a Modified Ketogenic Diet: A Pilot Study. J Proteome Res. 2020 Jan 3;19(1):382-390.

Nankova, B.B., et al. Enteric bacterial metabolites propionic and butyric acid modulate gene expression, including CREB-dependent catecholaminergic neurotransmission, in PC12 cells–possible relevance to autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103740.

Naviaux, R.K. Metabolic features of the cell danger response. Mitochondrion. 2014 May:16:7-17.

Nemecheck, P., et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptoms Improve with Combination Therapy Directed at Improving Gut Microbiota and Reducing Inflammation. Applied Psychiatry. 2020 Jul; (1)1.